Yopo & Cebil

Complete Guide to Yopo and Cebil Snuff & Seeds (Anadenanthera peregrina)

Last updated January 2021. Note that we are writing this article for educational and research purposes. We do not sell Yopo, we have never sold Yopo, and we have no idea where you can buy it. We also never intend to sell Yopo. We also do not recommend anyone to take Yopo. Our website aims to be an educational web resource where one can learn about ethneogenic topics and the traditional customs of Amazonian peoples which is the reason that we have written this article.

Table of Contents

What is the difference between Yopo and Cebil?

…

What is Cebil?

…

What is Yopo?

Yopo is a product of the plant species “Anadenanthera peregrina”. It is also called Cohoba, Vilca, or Cebil.

Its primary ethnobotanical usage is as a snuff, snorted for its effects. In order to give you a quick video introduction, you can watch this video:

History of Yopo and Cebil

These are some of the oldest recorded entheogens ever in North America.

The following text contains excerpts from Jonathan Ott’s book “Shamanic Snuffs or Entheogenic Errhines”. We recommend that you can find a PDF of that book online if you would like to learn the full details of his research on Yopo.

When one is ill they bring the buhuitihu to him as a physician. [ … ] He must purge himself like the sick man; and to purge himself he takes a certain powder, called cohoba, inhaling it through the nose, which inebriates them so that they do not know what they do; and in this condition they speak many things, in which they say they are talking to the zemies, and that by them they are informed how the sickness came upon [ the patient]. – Ramon Pane, Relacion acerca de las antiguedades de los indios [1496]

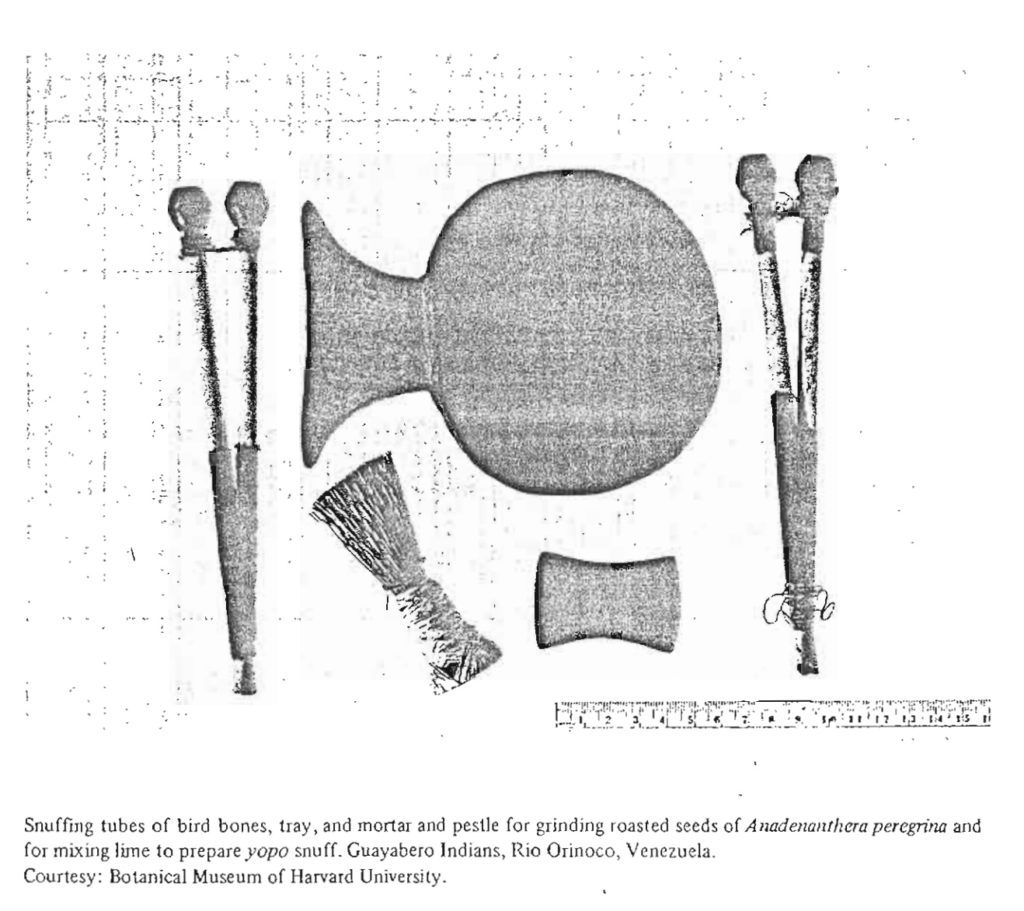

At the outset of the 19th century, the German naturalist Alexander von Humboldt navigated the Rio Orinoco, and studied the Otomac Indian-use of “fiopo”, described as a powder made from baked cakes of the levigated dough of maniocflour, snail-shell lime, and the broken, fermented pods of a legume that he named Acacia Niopo [Reichel-Dolmatoff 1975; Schultes & Hofmann 1980; von Humboldt & Bonpland 1819].

Roughly half a century later, the pioneering British botanist Richard Spruce made a careful study of the use of fiopo among the Guahibo Indians of the Colombia-Venezuela Orinoco-basin, supported by ample botanical voucherspecimens and a complete Guahibo-kit of fiopo-snuff paraphernalia. There was an initial error that the substance had just been tobacco, and not yet identified to be what we today know as “Yopo” in the western world which is a product from the “Anadenanthera peregrina” tree whiich was done in 1916 by the Usan ethnobotanist William E. Safford. Safford identified the tree by its usage in Haiti. The snuff is used both in mainland South America in the Northern part of the conteninent as well as in the Carribbean islands.

There were also early colonial repons of the use of vi;ca and cebll, at least the latter as a snuff. In 1559, J. Polo de Ondegardo [1916) wrote that the Incans of the south Andean highlands would “invoke the devil and inebriate themselves” for divinatory purposes with an herb called vilca, “adding its juice to chicha [fermented beverage of maize or another carbohydrate-source] or taking it by another route”.

The Taíno people were the indigineous peoples who lived on the islands of the Carribbean before settlement by Europeans, Africans, and other peoples from the old world. They were the original Carribbean peoples and their culture no longer exists today. They lived in modern day Cuba, Dominican Republic, Haiti, Jamaica, Puerto Rico, Bahamas and they used “cohoba” … which is yopo! They grew and cultivated the Yopo tree on their islands and made snuffs from it. We have limitied information about their contact with the peoples from Northern South America and if the intermixing of cultures allowed the spread of Yopo to be between both the islands and the mainland. The Taíno “culture” no longer exists, as they nearly completely interbred with both whites and blacks who came to live on their islands.

The indigineous people of South America who use Yopo are the natives who live in the Northern part of the continent, in Colombia, Venezuela just down to the northern border regions of Brazil. The Piaroa Indians of southern Venezuela are said to be «avid yopo inhalers», although they have to travel to savannah-regions to obtain their seeds, much like the nearby Colombian Makiritare, Piapoco and Puinave Indians. Piaroa may add ayahuasca (Banisteriopsis caapi (SPR. ex GRISEB.) MORT.) stems to yuwa or yopo-snuffs, and likewise chew caapi (or ayahuasca) while taking it [Castillo 1997; de Smet & Rivier 1985], also cited for the Pume of Venezuela, the first group documented to chew the roots of ayahuasca; while Makiritare-shamans put roots of kaahi (B. caapi) and aiuku (Anadenantherai)n their maracas[d e Civrieux 1980]. By the same token, the Waiki of Venezuela and Brasil, obtain seeds of A. peregrina ia trade or pilgrimage [Prance 1972], or else cultivate it near their communal malocas or shapunos.

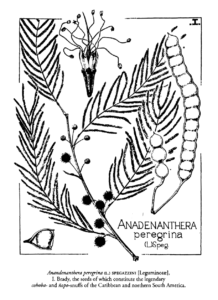

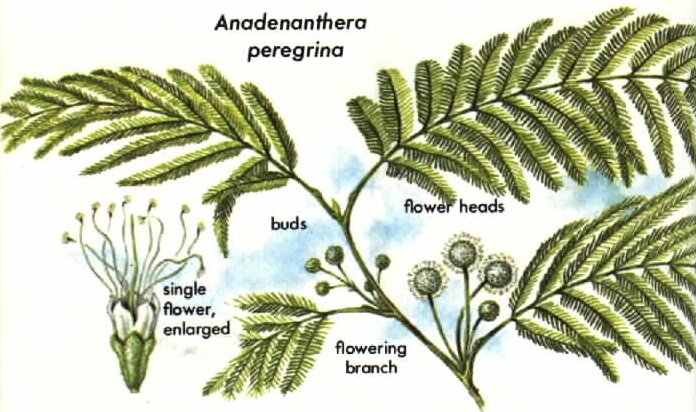

The Yopo or “ANADENANTHERA PEREGRINA” Tree

The yopo tree thrives in tropical countries. It prefers to live in drier areas in sandy and clay soils, rather than wet ones. The yopo tree likes savannas and and grasslands and open areas, growing naturally in Brazil, Guyana, Colombia, and Venezuela. Its growth has spread to the Carribbean islands, likely by humans bringing it there for its ethnobotanical properties. The ripe, dried seeds are easy to germinate and plant. The tree requires poor and relatively dry soil, which makes it easy to spread for culativation. It can be started in the moist tropics but quickly dies.

The tree will grow from 3m-18m in height. It has a gray to black bark that is often covered with conical thorns. The leaves are finely pinnate and up to 30 cm long. The flowers are small and globose. The leathery, dark brown seedpods, which can grow as long as 35 cm, contain very flat and roundish seeds that are reddish brown in color and 1 to 2 cm across.

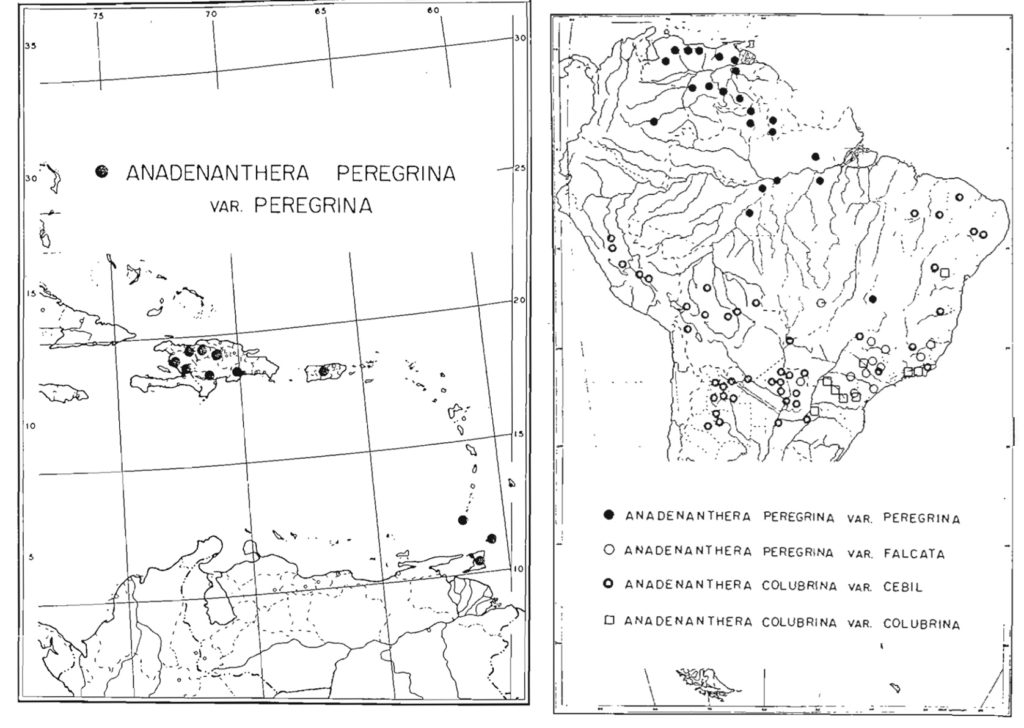

There are two geographically isolated varieties:

- Anadenanthera peregrina var. peregrina Altschul: northern Brazil to the Antilles

- Anadenanthera peregrina var. falcata (Benth.) Altschul: South America (in Brazil, only in

the east)

Archaeological records show usage in Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Peru, Haiti, the Dominican Republic, and Puerto Rico (Ott

1996). Under the name “cohoba”, it was mentioned many times by early colonial settlers, by Fra Bartolomé de las Casas (Safford 1916). In the early sixteenth century, Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo y Valdés was the first to note that the powder was obtained from the seeds of a tree belonging to the legume family (Torres 1988). The island of Cuba was apparently named after cohoba. The first botanical description of the tree was provided by Linnaeus in 1753.

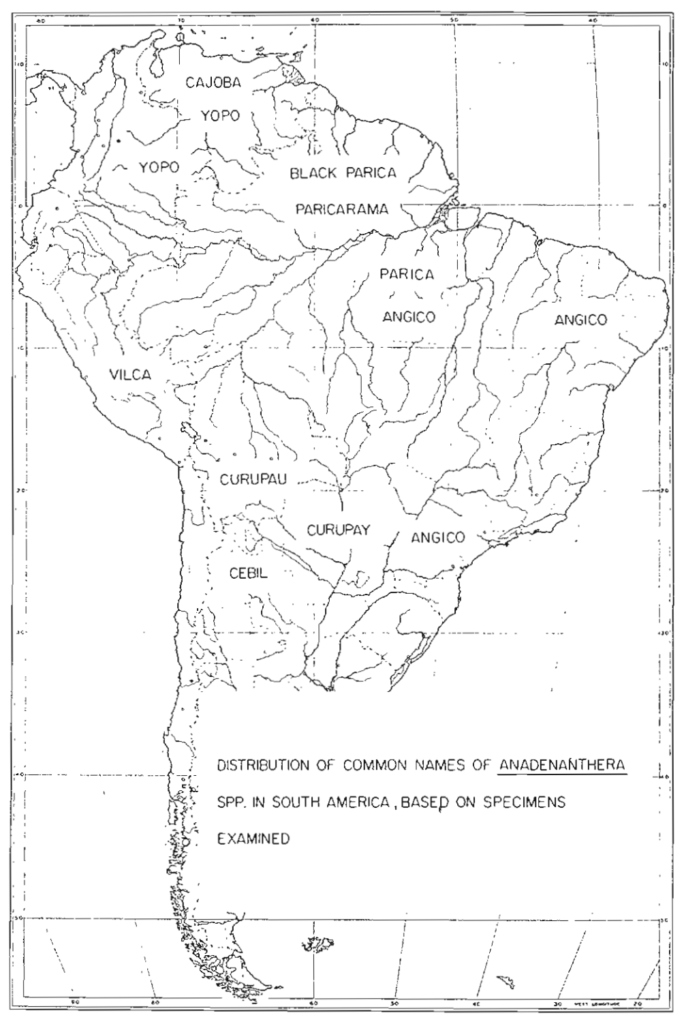

What are the many names of Anadenanthera peregrina?

Yopo, or Anadenanthera peregrina, is known by many different names. Even throughout the 20th century the snuff was referenced by many different names in literature that was written by academics and ethnobotany enthusiasts who were laymen. It seems to be that with the dawn of the internet many entheogens took on one primary name and the rest of the names fall into the background. Yopo was the name that seemed to universally “catch on” and all of the other names fell into the background – much alike how “ayahuasca” was taken on as the primary name of banisteropsis caapi from the 1990s onward and the other names like “yage” which were also used throughout the 1900s in the English speaking world fell out of popular use.

What is the relationship between Yopo and Ayahuasca?

Many tribes will chew on the ayahuasca vine while they consume Yopo. The two plants are not related taxonomically, and they

Distribution of the Yopo tree across the Caribbean and South America

There is some confusion between the names of various different snuffs, and throughout history there are a lot of words thrown around that may have just been used for generic snuffs. “Epena”, for example, once meant to just be a generic term for any snuff or rapé – including tobacco or virola or yopo, but today it refers only to the Virola visionary snuffs which are made out of completely different plants. We have a complete guide to Virola and a complete guide to rapé that should better describe those types of snuffs and how they are distinct and different from Yopo.

The above map shows that there are many different names, but to specifically note the archiac names. Today, Angico never refers to Yopo, it is always the “Parapiptadenia rigida” plant, and Paricá is also no longer Yopo, today it is the “Schizolobium amazonicum”.

What are the effects of Yopo/Cebil snuff?

Psychoactive effects and alkaloids

What are the health risks of Yopo/Cebil snuff?

…

What is the difference between Yopo and Cebil?

…

How to prepare Yopo/Cebil snuff

Yopo preparation with Lime from Snail Shells

One interesting component is that lime is used in the yopo recipes.

Method one – dry it out

- Take the yopo seeds and dry them out and roast them

- Powder them

Method two – fermentation

- Take the yopo seeds and

Video guide to Yopo snuff preparation

What is the legality of Yopo/Cebil Seeds and Snuff?

Is Yopo/Cebil legal in Canada?

Yes. It is not explicitly prohibited by law and there exists websites (not ours) and shops that sell it.

Is Yopo/Cebil legal in the United States?

Mostly.

Neither Anadenanthera colubrina, Anadenathera peregrina nor any other Anadenanthera species are controlled species in the United States. Live plants and seeds are often sold and grown. However, DMT, one of the chemicals contained in the plant, is Schedule I in the U.S. Practically, this means that if an extraction is done on DMT containing Anadenanthera species, the resulting DMT is illegal to possess. We are unaware of any cases in which an individual has been prosecuted simply for growing a plant or for doing a home extraction of a plant, although it seems quite possible that a few such cases exist.

However, Yopo is specifically outlawed in the state of Louisiana. Effective Aug 8, 2005 (signed into law Jun 28, 2005) Louisiana Act No 159 makes 40 plants illegal, including A. peregrina and A. colubrina, when intended for human consumption. The law specifically excludes the “possession, planting, cultivation, growing, or harvesting” of these plants if used “strictly for aesthetic, landscaping, or decorative purposes.”

Yopo was almost made illegal in the state of Tennessee, but instead they only made Salvia Divinorum illegal. Tennessee had proposed a bill that would have banned dozens of plants as “hallucinogenic” when intended for human consumption, but it didn’t pass.

However! There is an anecdotal report on reddit where some guy did get charged for having Yopo seeds. Read the post directly here. He claims that he was arrested and the seeds were confiscated and taken to a lab for a Gas Chromatography/Mass Spectrometry test, where they can see what alkaloids are present inside. They found that there was Bufotenin inside, and as such charged him for possession of a schedule I drug offense. Here is his quote:

At first the judge wanted to give me a 3 year suspended sentence.

After a shitload of pre-trial conferences and after paying tons of money to my lawyers, the best deal I could get was 2 years probation with substance abuse counseling.

The judge said the max penalty for simple possession is 5 years in prison.

Where can I buy Yopo/Cebil seeds in Canada?

We do not sell them and do not know where you can source them. Considering the undetermined health effects of Yopo and legality, we cannot recommend that anyone consumes it.

How is Yopo used by indigenous people?

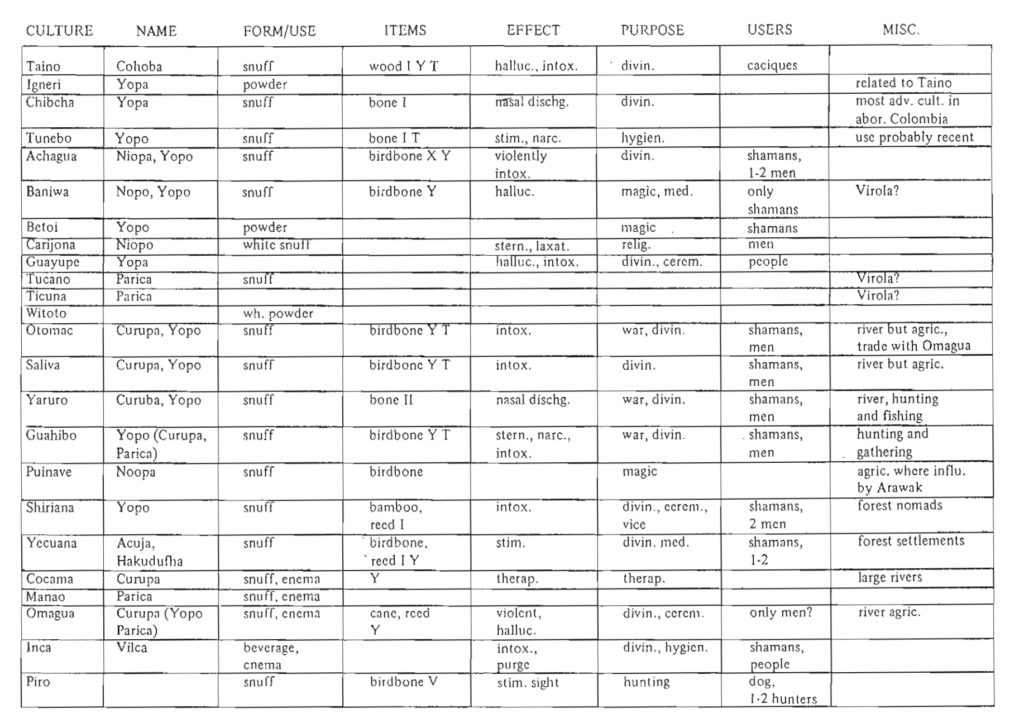

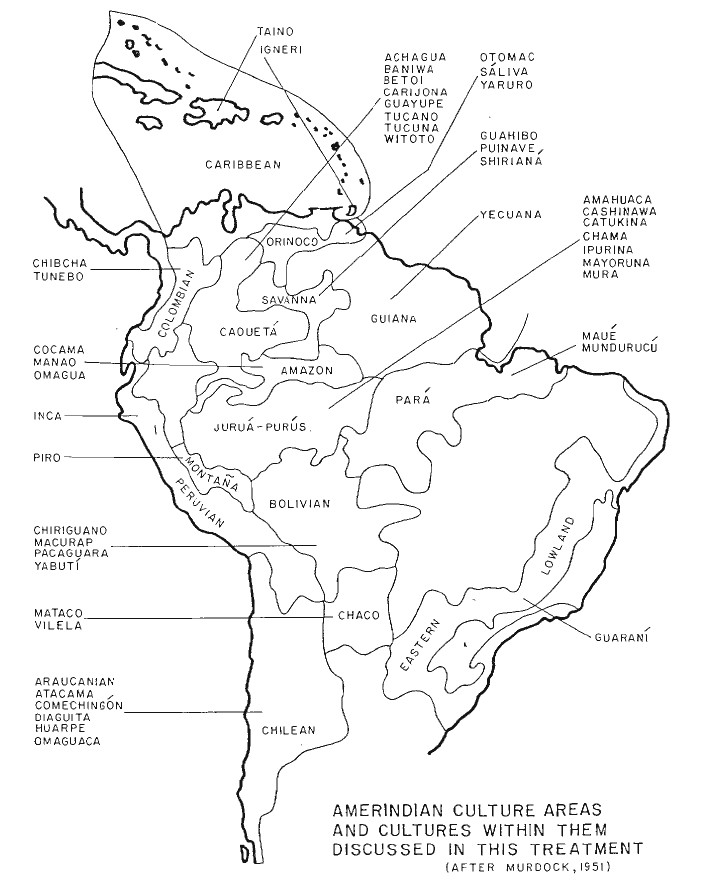

Chart of Yopo’s uses across Amazonian cultures

You can click on the above chart to be taken to the full-sized image of it. It details a comprehensive look at how people of many different south American cultures all consume Yopo in their own ways.

Yopo/Cebil Ceremony

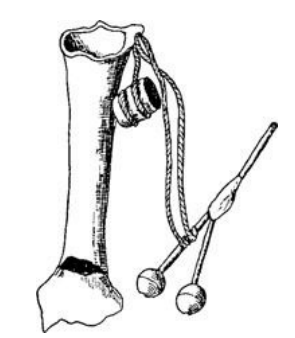

The primary usage of Yopo is in the preparation of snuffs, meaning plant powders based on the plant which are blown into the nose. Blowing the yopo into the nose will cause effects to the recipient, which are involved in hunting rituals and other types of activities. There are lots of videos online, including that we have put in this article, that show what that process lookings like in seemingly authentic experiences. It is usually blown with either a small bone tube, or a really long bamboo one such as pictured above.

Here is a few embedded videos of Yopo ceremonial activities for you to view.

More Yopo Details

We have contemporary documentation of the Guahibo-preparation and use of yopo, following in the footsteps of that pioneer Richard Spruce. The Cuiva-Guahibo of the Venezuela-Colombia border-region on the Rio Kapanapare make tortillas of the dough of crushed topa (yopo) seeds mixed with waruro, snail-shell lime, and carefully heat them to dryness. This is rendered into a fine powder and insuffiated via a hollow bone which does not exceed 5g in size.

Orinoco, Venezuela. (From Hartwich, Die menschlichen Genußmittel, 1911)

The Kubeo of northwest Amazonia are reported to employ two types of visionary snuffs [Goldman 1963]. The first, kuria, is made from the bark of the kuri-dku-tree, undoubtedly Virola [Schultes 1954], but the second, dupa, is made from the resin of the amhokuku-tree-might this possibly be the resin of Anadenanthera.

In Andean Bolivia, a poorly-characterized resinous incense is called zumaque or zumuque-these are Chiriguano- and Callawaya-names for the yopo plant [de Lucca & Zall es 1992; Oblitas Poblete 1992], the resin of which is still used ethnomedicinally by the Chiquitano of the Bolivian lowlands, who call this tree “nosirr” or by its Tupi Guarani- name, “curupau” [Birk 1995]. Schultes [1954] has also commented on a mysterious, amber resin, called paricá in the Colombian Amazon, supposedly from a large forest-tree, once widely used as a shamanic snuff. It is evident that paricá, like epená, is a generic rather than a specific name for shamanic snuffs, and both names have been used traditionally for Anadenanthera, Virola nd numerous other snuffs. Today, Paricá no longer refers to snuffs specifically but is a common name for the Amazonian ornamental tree known as “Schizolobium amazonicum”.

Amazing 100-page book resource that highlights how many different tribes each use Yopo

LINK TO THE BOOK – DOWNLOAD HERE

This document was written by Siri Sylvia Patricia von Reis (born February 10, 1931), she is an American botanist, author and poet. She is of half-Finnish and half-Swedish ancestry. She has worked as an investigator at the New York Botanical Garden.

In 1972 she published a document called “The Genus Anadenanthera in Amerindian Cultures“. It is credited as being written by Siri Altschul, however Altschul was the name of her husband who she ended up divorcing not too long after the book was published.

If you are hungry for more yopo content and would love to know the details about how native peoples used it in detail, this book will answer all of your questions.

Detailed Yopo/Cebil snuff usage by Amerindian tribes of the Caribbean and South America

In this section we detail much of the information that is featured in the document called “The Genus Anadenanthera in Amerindian Cultures“. We credit Altschul/von Reis with the full source primary source of information, and we are displaying it here for educational purposes only. Considering that the document was originally published in 1972 and in a format that is not accessible for the web, we are opening up the information in an indexable way for the web for educational purposes only and no commercial intent – as we do not sell Yopo in Canada and we want to encourage education about traditions of indigenous peoples of the Americas which have been forgotten.

Caribbean culture’s traditional Yopo snuff usage

Taino culture

…

Igneri culture

…

Colombian culture’s traditional Yopo (Anadenanthera Peregina) snuff usage

Chibcha culture

…

Tunebo culture

…

Caqueta culture’s traditional Yopo (Anadenanthera Peregina) snuff usage

Achagua culture

…

Baniwa culture

…

Betoi culture

…

Carijona culture

…

Guayape culture

…

Tucano culture

…

Tucana culture

…

Witoto culture

…

Orinco culture’s traditional Yopo (Anadenanthera Peregina) snuff usage

Otomac culture

…

Saliva culture

…

Yaruro culture

…

Savanna culture’s traditional Yopo (Anadenanthera Peregina) snuff usage

Guahibo culture

…

Puinave culture

…

Shiriana culture

…

Guiana culture’s traditional Yopo (Anadenanthera Peregina) snuff usage

Yecuana culture

…

Amazon culture’s traditional Yopo (Anadenanthera Peregina) snuff usage

Cocama culture

…

Manao culture

…

Omagua culture

…

Peruvian culture’s traditional Yopo (Anadenanthera Peregina) snuff usage

Inca culture

…

Montana culture’s traditional Yopo (Anadenanthera Peregina) snuff usage

Piro culture

…

Jurua-Purus culture’s traditional Yopo (Anadenanthera Peregina) snuff usage

Amahuaca culture

…

Cashinawa / Kaxinawa / Huni Kuin culture

…

Catukina / Katukina culture

…

Chama culture

…

Ipurina culture

…

Mayoruna culture

…

Mura culture

…

Para culture’s traditional Yopo (Anadenanthera Peregina) snuff usage

Maue culture

…

Mundurucu culture

…

Bolivian culture’s traditional Yopo (Anadenanthera Peregina) snuff usage

Chiriguano culture

…

Macurap culture

…

Pacaguara culture

…

Yabuti culture

…

Chilcan culture’s traditional Yopo (Anadenanthera Peregina) snuff usage

Araucanian culture

…

Atacama culture

…

Comechingon culture

…

Diaguita culture

…

Huarpe culture

…

Omaguaca culture

…

Chaco culture’s traditional Yopo (Anadenanthera Peregina) snuff usage

Mataco culture

…

Vilela culture

…

Eastern lowland culture’s traditional Yopo (Anadenanthera Peregina) snuff usage

Guarani culture

…